- Home

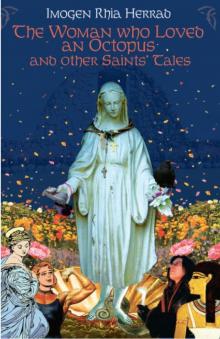

- Imogen Rhia Herrad

The Woman who Loved an Octopus and other Saint's Tales

The Woman who Loved an Octopus and other Saint's Tales Read online

Contents

Title Page

Cofen

Madryn

Annon

Melangell and Dwynwen

Arganhell

Eiliwedd

Eurgain

Indeg

Collen

Winifred

Non

Tydfil

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

The Woman who Loved an Octopus and other Saint’s Tales

Imogen Rhia Herrad

Cofen

Sixth century

Also known as Govan or Goven. St Govan is best known for the chapel wedged between rocks by the sea in which the saint is supposed to have lived as a hermit in the sixth century. When pirates attacked, Govan hid inside a rock that miraculously closed around the saint, opening up again only when the danger had passed.

In fact the famous chapel was only built in the thirteenth century, as far away from St Govan’s time as our own. But the altar and a seat cut into the rock are much older and may well date back to the sixth century. Even older was the healing well which used to rise near the chapel, providing fresh water.

Commonly St Govan is assumed to be a man. But there is a story that the person who lived by the sea, tending the holy well, was a woman named Cofen, and maybe no saint at all.

The sea is still and grey and green. A breeze strokes my skin and moves on. The sky has covered its face with clouds. I’m cold.

This is where we first met. I’d never been to this place before. I needed to get away from the city and the people and the chemicals in the air. I needed to breathe.

So I drove to the sea. I parked the car somewhere and clambered down the rocks until I stood on the shingle and breathed salt and seaweed and sand and freedom. There were mermaids singing far out in the water, and the wind put on a dress of whirling sand and danced with me.

The tide came in. I sat on the sand near the water and breathed with the waves, in and out, in and out.

The mermaids’ song became wilder the higher the tide rose. And then suddenly there was someone else. There was a bluegreengrey shape in the water, a shimmering and glistening shape with many arms and the deepest eyes in the world. She was watching me. She was there in the water, watching me sitting on the shore.

She was sinuous and sensuous. Her skin shimmered dragonfly blue, aquamarine, pebble grey. She pulsed like a sea anemone. Serpentine arms rose and fell with the breathing of the waves. Her soft tentacles arched. They beckoned to me. My skin shivered with longing for her touch.

She moved closer.

I jumped up and ran away.

I didn’t go near the sea for weeks.

I dreamed of it every night. I dreamed of water sparkling silver with sunlight, of pebbles smooth and green and slippery with algae. I dreamed of seaweed streaming like long hair in the current and warm, wet tentacles; softer than water.

Every morning I woke up with the taste of salt on my lips.

I tried to stop it, but the waters rose and rose and there was nothing I could do to resist them.

In the end I gave in and went back to the beach. I parked the car in the same place and clambered down the rocks and dared the sea to come and get me. I resented its pull. I had never felt anything like it. I had always been my own person, from the first moment of my life. I never had a mother. I wasn’t born like other people. I hatched out of an egg.

‘Come and get me then,’ I said to the sea. Far out, there was a bluegreengrey shimmer on the water, like sunlight. But it was a dull day.

The water rose. The tide was coming in. It rose and rose and rose. The waves climbed up the beach, over the sand, over the shingle. I trembled with anticipation. Water touched my shoes, flooded over my feet, climbed up my thighs. Something that felt like a warm, wet finger stroked my leg. Then another. And another. Eight soft bluegreengrey tentacles wandered over me, exploring, touching, stroking.

She tasted of salt like the sea.

Like the sea, she hollowed out my defences. I should have known. The sea reduces cliffs to sand. What chance did I have?

I had a mermaid for a mother. She loved me, but she loved the sea more. One morning I woke up and she was gone. I waited and waited and waited, but she never came back. In the end I gave up and crawled into an egg and stayed there for a long time until somebody put a broody hen on it to see what would happen.

I was captured in the eight arms of my lover. Her beauty captivated me. She taught me how to breathe under water. She didn’t need to, every kiss she gave me was a kiss of life.

Together we explored the ocean. Being with her felt like flying. I forgot about air and land and solid ground. I lost my taste for fresh water and became a creature of the sea. We feasted with sharks and dived down to the very bottom of the sea where the kraken lives. Every night, we slept on sand as soft and white as linen sheets. She braided shells and corals into my hair. She found a way into my heart and I didn’t know how to get her out of it.

So I left the sea.

But it’s not so easy to rid myself of her. She put a spell on me so that I cannot forget her, although I have tried every way I can think of.

I had an ogress for a mother. She had wanted me to be an ogress too because she hated people. She wanted me to come with her when she went to kill and eat them. But I wasn’t an ogress and I wasn’t like her although I tried and tried. She went away to look for another daughter. I waited and waited and waited, but she never came back.

It’s cold by the water. The sky has covered its face with clouds. The sea is still and grey and green.

I come here every day to teach her to leave me alone. I will not go back into the water. I will stare her down when she comes too close to show her that there is no feeling left.

The pebbles on the beach look like eggs, smooth, oval. An egg is like a world of its own. Self-contained. No way in, no way out. Perfect. To achieve contact, you have to break the shell and destroy it. There is no other way.

Nobody is going to break me.

The mermaids are singing again, far out in the bay. I don’t want to hear them. I push my hands over my ears and scream at them to shut up and go away. There is a bluegreengrey shimmer in the water. It’s only the sun, but I scream at that too. I want the whole world to go away and leave me alone.

A blue tentacle is stroking my heart and I can’t breathe.

I had a soldier for a mother. She was fierce and brave and killed many people in the war. Killing was her job. It was all she could do. When she came back home from the war, she took her gun and she killed me. I waited and waited, but she didn’t kill herself to be with me.

It’s raining. I sit in the shelter I have built for myself and watch the rain hit the sea. The tide is coming in, but it can’t come as far as where I’m sitting. I made sure of that. I won’t be captured again. I will sit here out of reach until she’s learned that she can’t get me. Then I will leave and not sooner. I don’t want her to forget me. I want her to know that she can’t have me.

The waves come creeping nearer. And nearer. The waters rise and rise. A bluegreen shimmer beckons.

I turn myself into a rock. I look on, unmoved as stone, as she tries and tries to get near me. Nobody gets near me.

And when the tide turns at last and the water recedes, I hurl all the rocks and pebbles I can after it to make it stay away. I want to build a dam around me to keep the water out forever.

But a stone is stuck in my throat and I can’t breathe.

I will not cry. I will not cry. I beat my hands

on the rocks until they bleed. That will give you something to cry for.

I had a bitch for a mother. She was nice some days and on others beat me black and blue. She shut me in a cupboard for days without food. Pembroke Social Services have a file on her but it wasn’t enough to take me away from her although I begged to be taken away. When she heard about that, she was devastated that I did not want to stay with her, and I felt terribly guilty. I did not know how to keep her out of my heart.

She is still alive. She lives in a rest home and people think she’s a nice old lady.

I turn my back on the sea and walk inland. I walk and walk and walk until I’m tired enough to drop, but not tired enough to sleep. Whichever way I turn, I’m going towards the beach. There are webs between my fingers and I can’t unlock the door of my car when I finally find it.

The waves call my name and the mermaids are singing. Their voices follow me, travelling on the wind.

A green tentacle strokes my heart.

I clamber down the rocks until I stand on the shingle and breathe salt and seaweed and memory. The water has risen higher than my shelter. She comes gliding towards me, walking on the water.

She is sinuous and sensuous. Her skin shimmers dragonfly blue, aquamarine, pebble grey. She pulses like a sea anemone. My skin shivers with longing for her touch.

I swim towards her.

Madryn

Fifth century

Madryn or Madrun was the daughter of Gwrtheyrn (or Vortigern), the British king who invited the Saxons into Britain to help fight off the Picts and other sea raiders. When it turned out that the Saxons were a bigger threat by far, his own people turned against Gwrtheyrn and he had to flee with his family. Madryn, her baby son Ceidio, and her father sought refuge in a wooden fort on the Llyn Peninsula, which was set alight. Gwrtheyrn died in the fire. Madryn managed to get away with the child in her arms, and fled from the troubles in Wales to another country.

The sky is red. Somebody fires a shot in the street. I spin around, drop the shopping bags I am carrying, crouch down for shelter, try to locate the sniper. People turn and stare, somebody laughs.

The doctor says there is no shooting here, she says it is a car backfiring, fireworks, nothing to worry about.

How does she know? I ask her. How does she know? There was a man shot in this city last week, a girl in the hospital told me about it, she read me an article from her newspaper. People are being shot dead in your city, I tell the doctor. How do you know nobody will be shooting at me?

Because we are not at war, she says. You are not in the war anymore. Sometimes people get shot, yes, but it is rare. It does not happen often.

But it does, I say.

Not often, she says. You are safe here.

I say nothing. I look out of the window of her room. There is a little bit of grey sky with birds in it, and black roof tops. In her window, the sky is grey. In this room, where I come twice a week to talk, I am almost safe, for a while. This room is in the doctor’s world where people are safe, where the sky is grey, where there are no shots, only fireworks.

I would feel safer if I still had a weapon, I tell her. I fought at home when we were invaded, right up to the birth I fought. I was a good fighter. People were afraid of me. I was somebody then. I was the king’s daughter, and a fighter in the field. I was strong and proud. I had my weapons, and even though there was war and fighting and killing, I felt safer then than I do now.

Weapons kill, she says.

Yes, I say. I feel naked without a weapon. Skinless.

Then I say nothing and look out of her window again, and there is a new silence in the room.

* * *

How is your baby? the doctor asks.

Still in the hospital, I say, which she knows. Recovering, I say, which means nothing.

I don’t say: I have a baby with bandages for a body. Bandages for a face. No mouth, no nose, no eyes.

I don’t say: They’re going to try another skin graft next week but they don’t know if it’ll work this time.

How is your baby? the doctor asks, and I flinch. The question sounds like an accusation.

* * *

When I was first taken to this room to talk I expected somebody who would want answers from me.

I wondered what I should do. To say nothing is dangerous. When you say nothing, it means that you will not co-operate.

To say too much is dangerous. People will become suspicious if you talk too willingly.

I was surprised that the questioner was a woman. The other doctor had only told me that he thought it would help me to see a specialist. A therapist. He said the word slowly and looked at me, drawing breath to explain to me what a therapist does. I should have let him. It might even have been amusing to listen to him talking in terms he thought suitable for me, the refugee from a primitive, war-torn country: soul doctor and bad spirits that needed driving out of my troubled self.

A therapist, I said. Ah well. I would have preferred a Jungian analyst. Still, we can’t have all we want, can we?

That shut him up. Later though I wished I hadn’t said it. To speak without thinking means you have less control over what you say. Now they know that I know about therapy and analysis, that I might be able to see through some of their simpler tricks. I have given myself away. They will have to use the big guns now and I might not be able to withstand those.

When it was time for the first session, I forgot about my decision to appear to allow myself to be drawn out, to talk, apparently reluctantly, slowly, but to talk. I just sat and looked at her. I listened to what she said, not to her words, but trying to find the sense behind them. I wanted to sniff out her intentions, tried to work out what it really was she wanted to find out.

* * *

She rarely asks questions. More often, she will just sit and look at me, or out of her window, or to a point just to the side of me. At first I worried that she was giving a signal to somebody. But behind me is nothing but a blank wall.

I am trying to understand why you are so afraid, she says.

I don’t like her asking questions. I am trying to understand you means I am trying to look inside your head so that I will know which levers to pull.

I decide to challenge her. Why? I ask back.

She wrinkles her forehead, appearing to give my question thought.

Because I feel that there is something in the way, she says. We seem to be running on the spot without getting anywhere.

I am pleased to hear this. I have been successful in resisting her, but she doesn’t seem to have noticed that I’m doing it on purpose. She thinks it’s because I’m afraid.

Unless it’s a trick. It might well be a trick, lulling me into believing she is worried, into believing I have tricked her when she sees through me perfectly well.

Why do you think I’m afraid? I ask.

She leans forward over her desk, looks at me earnestly. She had wanted me to sit in a corner of her office, on the sofa or an armchair, and she would have sat in the other armchair. She said it would be more relaxed. But I said I preferred her sitting at her desk. I said it was more professional, but the truth is that I prefer to have the desk between her and me. It gives me a small advantage in case I have to run away.

You have been through terrible things, she says. The invasion, the war, your father dying, your baby wounded in the fire.

I hate being reminded, having my nose rubbed in my infirmities, my misfortunes.

So, she says, I would expect you to be traumatised, of course.

I hate being told that I conform to her expectations. Why does she need me to tell her anything at all if she knows everything about me anyway?

In fact, she says, you have come through this remarkably well. You managed to save yourself and your son.

That means: you’re not that badly traumatised, you don’t warrant all that much help and sympathy. You can look after yourself after all. You’re tough.

But, she says, there appears to be someth

ing more specific. There is something sharply defined that you appear to be terrified of. I would expect you to be hypersensitised generally, which you are. But there is something more than that. At least that is my impression.

She leans back again. This, she explained to me at the beginning, is so as not to crowd my space.

I prefer it when she shows emotion, because then I can read her more easily.

What do you think there might be? I ask her. It might give me an idea of what she thinks.

I don’t know, she says. Only you can tell me.

Why should I, I say, my voice flat. I hadn’t meant to say that, certainly not in the way it came out, as hostile as that.

She says nothing. She is good at saying nothing.

To break this silence would be to give up, to give in, to wave the white flag and signal surrender. I would have to trust her blindly, put my fate, my past and my future, into her hands.

I say nothing.

She says nothing.

I think of another room, another questioner, another me.

* * *

I want to scream at the doctor. You don’t understand at all, I want to scream. You have no idea. No idea. You think the world is safe. You have never been in a war. You don’t understand. The fact that I can sit here and not tell you anything means I trust you enough to believe that you’re not going to have me punished for not co-operating.

But I would rather cut off my thumbs than tell her that.

* * *

The sky is red. In my dream, I am running, stumbling, my lungs burning with smoke. I know that I am dreaming but it makes no difference. The night it happened, I kept telling myself that it was all a nightmare. I ran away from the fire with the screaming baby and told myself, this is not really happening, it is only a dream. But it wasn’t. It was real and it never ended. It still goes on, and my dreams are more real now than my waking hours in this grey country where people tell me that life is safe. I can hear the baby’s screams. They pierce my ears like an electric drill.

The Woman who Loved an Octopus and other Saint's Tales

The Woman who Loved an Octopus and other Saint's Tales