- Home

- Imogen Rhia Herrad

The Woman who Loved an Octopus and other Saint's Tales Page 3

The Woman who Loved an Octopus and other Saint's Tales Read online

Page 3

I broke my silence again, offering up a prayer for forgiveness at the same time. ‘Perhaps He is calling you.’

‘Us,’ she repeated. ‘She, He – it doesn’t matter. She’s calling you and me.’

‘That is absurd,’ I said, and added as an afterthought, ‘I have renounced the world.’

‘You can renounce the world without fleeing from it.’

‘I am not fleeing from it. I have come here where it’s quiet and far away from most things.’ How would she understand? How could I share a vision with this hippie? I never see visions. I am not given to them. ‘I feel closer to God here than anywhere else.’

‘God – the Goddess.’ She tipped her head back, opened her arms wide. The morning sunshine lay on the planes of her face. ‘They’re only names. You have been led here. By God, you would say. By the Goddess, I would say. By the Creative Spirit who is neither male nor female, who resides in all of us.’

The Spirit. I must subdue my spirit.

‘You must follow it,’ she said.

No, no, no.

I want to stay here.

Here, where the neversleeping sea is my heavenly bridegroom, where the yellow flames of the gorse speak in tongues in my ear. I have found the garden of Eden, and you want to banish me from it, lead me into a world that is full of serpents.

‘We have been chosen!’ she declared, almost gloating. I remembered how she had said, yesterday, ‘I was hoping for a miracle. And now I’ve got one.’ This was why she’d come here. Blatantly. Going to a holy place looking for a miracle. Taking a short cut. Not preparing herself, waiting in patience and humility until it pleased God to elect her; but pushing, rushing forward until she was in the front row.

Buddhist retreats.

Goddess worship.

A miracle hunter. She probably put her visions on the internet.

The fact that I shun the world does not mean that I am unworldly.

She won’t get far, I thought. Then remembered that she had already got exactly where she wanted.

I was exhausted. I felt as though I was fighting her for my life on the island.

I started climbing the mountain. My feet stumbled. I looked down.

I was walking, not on coarse short grass, but on a smooth, black surface. A tarmac road. A great wind came rushing down from the hills, bringing with it land smells of wet earth and leaves and grass.

The wind was humming and sighing and singing in my ears, lifting up my heart.

I do not want to go back into the World.

I felt as though with each step I made, I covered a mile.

The World is full of noise and distraction, destruction and falsehood.

A bird sang from somewhere, hidden in a tree. A dog barked.

I want to stay on this island. Everything I want is here.

I had left the island. I was walking on the road that He had laid down for me. Clouds moved across the sky. I was being propelled towards the mountains at great speed. Fine rain touched the skin of my face, my arms. On the island, I had been walking in hot sunshine.

The mountains drew closer together. A valley opened in front of me. Long, dried-up grass stalks in yellows and browns, green leaves; beyond that, grey and purple peaks.

Build my church here.

Stones appeared from nowhere. Great blocks of rock, the colour of the mountains. A tidy stack of slates, the colour of the sky. I heard the whine of a cement mixer, saw figures run to and fro. Scaffolding appeared. The sun was hot on my arms and back.

I was sitting on the mountain outside the Saint’s cave. On the far horizon, a ragged bank of peaks stood grey and purple against the sky.

Now I knew where. I still did not know why.

Because it is the will of God, I told myself. That should have been enough for anybody. It should have been more than enough for me.

Who was I to question the will of God?

Who was Jacob to question the will of God? I was Jacob. I was in the desert at night, alone. It was cold. The wind whistled and sighed. A shadow rose up next to me, and I clasped it and fought it and finally overcame it. I forced the struggling form down onto the sand, and in the orange light of the rising sun examined its face.

It was my own face that looked back at me. I was looking up at my own face.

‘I’ll be leaving the day after tomorrow,’ she said as we were walking away from the chapel that evening after service.

Sunlight lay on the water like a wide, shining road that appeared to connect us with the mainland.

We reached the fork in the road. She stopped and turned towards me.

‘What will you do?’

It was quiet, so quiet. The evening breeze whistled all around us. The waves sighed. From far away, I heard the call of a seagull.

I thought of the voice that I had heard.

I thought of the visions I had been given to see.

I thought of green and golden stalks of grass, purple mountain peaks.

A great noise filled my ears. It was the sound of my blood rushing through me, of my heart beating.

Melangell

Died c 590

Melangell was an Irish princess who fled to Wales to escape an unwanted marriage. She lived in the wilderness for fifteen years, until her solitude was disturbed by a prince hunting. The hunted hares sprang to her for protection, and Melangell caused a miracle to happen: all the hunters found themselves rooted to the spot, the huntsman’s horn frozen to his lips.

After she released the hunters, the prince granted her freedom from any molestation in the spot she had lived in for so long. Hares are known locally as ‘Melangell’s lambs’.

Dwynwen

Fifth or sixth century

One of the fifty sons and daughters of King Brychan. A certain Maelor wished to marry her but she rejected him. She dreamt that she was given a drink which delivered her from him, and which turned Maelor to ice. She prayed that he be unfrozen; that all lovers should find happiness in each other (or else be cured of love); and that she herself should never marry. She is – somewhat surprisingly – the patron saint of lovers in Wales. She founded a nunnery on Llanddwyn Island off Anglesey, and was invoked for the curing of animals.

D

I grew up in a big house, a large family. Brothers and sisters everywhere you turned, and lots and lots of servants, and I thought I’d never ever get away from there.

I was a loner.

No. I tried to be a loner. When my sisters and my friends played Weddings and Happy Families and Smacking the Naughty Baby, with their dolls, I sat in the grounds under a bush and played Being Alone. For it really to count, I had to turn slowly all around in a circle and not see anybody. Usually I cheated by keeping my eyes shut.

My father liked to call himself the King of the District. He was an Important Man, and he liked his daughters to make themselves useful by cementing business and political alliances; oiling the wheels of fortune and finance.

So I knew that at some point in the future, my time would come, no getting away from it.

I wanted to get away from it.

I very much did not want to be married.

Nobody understood that.

You’ll get used to it, my mother said. Everybody gets married sooner or later.

These are different times, I argued back, the Great War over and the old Queen long dead and the Pankhursts triumphant. She did not know what I meant. She’d never even heard of Women’s Suffrage.

Some of my older, married sisters narrowed their eyes and said they didn’t see why I should be spared when nobody else was.

My father – in a good mood – laughed and said nonsense, of course you will, I bet you’ll get used to it – with a nasty twinkle in his eye. He did not have much imagination, and he was not a nice man. But he was amused, and slapped me fondly, twice.

Some of my younger sisters laughed at me; they were looking forward to the big day, the beautiful new clothes and the reception and the honeymoon; all the atten

tion they would receive.

I thought of the days and the nights afterwards, the rest of my life.

M

I had heard of her, of course. The story had travelled, even across the water, even into rural Ireland. Especially into rural Ireland.

Women would tell of her and her unwanted bridegroom, encased in an impenetrable block of ice. And though the people tried and tried (so the story was told) with hammers and chisels and blow torches – they couldn’t get him out.

A miracle.

It takes a miracle where I come from to get you out of an engagement, believe me.

Not everybody believed in the miracle.

Or even in her.

They thought it was just a story, make-believe; a sop; not something that had really happened.

Some said that even if it had, she’d be dead by now, she’d died years ago.

I grew up in her shadow. In her light.

I wanted to meet her. I believed I would, one day. I could never picture her dead. How could she be dead when I was here, waiting for her?

I’ll never forget the day my father brought the suitor home.

That’s what he called him: I have a suitor for you.

He rang from his office, spoke to my mother and told her to prepare an extra special dinner, then told me to get my best frock out and wear it that night.

In the evening, he brought the man home, a business associate, much older than me, not much younger than my father. I don’t think I said a single thing to him all evening except How Do You Do and More Sauce? And Good Night.

I don’t think he noticed. He and my father talked throughout the meal – of business, of golf, of hunting and politics. He held muteness to be a virtue in a woman. He told my father that he thought I’d make him a good wife.

It should have brought me nearer to her, having an unwanted fiancé of my own. But it didn’t.

I could feel her sliding away from me; feel my dream – of getting away, of going to meet her one day – slide out of my grasp and flow away, out of reach, almost out of sight.

Almost.

This is the end of me I thought when my father rang again, some weeks later, to relay the man’s proposal.

His words, not mine.

He has asked me to relay his proposal to you.

You wouldn’t think it happens these days, but it does; oh, it does.

I found my tongue shrivelling in my mouth. I found I was incapable of pronouncing the word No.

I said nothing, which my father interpreted as consent.

This is the end I thought. He will marry me and I will cease to be me and become his wife. I will cease to be me and become a Good Christian Woman.

I did not believe in her miracle any more.

D

My rage and my determination grew stronger and stronger.

The stronger they grew, the smaller they became.

I could feel the strength grow until it was nothing but a tiny dot inside me, as white and as hot as iron in the village blacksmith’s fire.

I felt a thunderbolt grow inside me the way I could see children grow inside women’s bellies; although I was not supposed to know how they got there.

The stronger it grew, the smaller it became. I grew white and silent while the thunderbolt increased its strength. I thought I would have to burst with it when its time came, burst and fly asunder like a ball of fire, showering destruction.

I met Maelor Williams one evening at a dance where mothers took their daughters to be sold into marriage.

He was charming enough as men go, left my toes almost intact and occasionally even made me laugh with his stories.

He said he liked me. Maybe he did.

But when he asked could he court me, I said No.

It was not a word he was familiar with.

And it didn’t stop him, of course. He kept trying, with his dancing and his pleasant words, his chest puffed out like a cockerel’s. And when even he could see that that was no good, he led me into the rose garden one night and pinned me against the romantically crumbling old wall.

I asked you a question once, he said, and you gave me the wrong answer. This is your chance to get it right. Will you marry me?

I didn’t know what to do.

First I tried to laugh.

Then I tried to reason.

Then I tried not to be very frightened.

The thunderbolt inside me went white cold with rage.

I freed myself from his grasp and froze him with a glance.

I mean literally.

From one minute to the next, Maelor Williams was encased in a block of ice.

I was free.

M

I did not believe in her miracle any more, but there had to be another way. In the end I chose the simplest. I ran away.

I did what hundreds and thousands of Irish girls must have done. I crossed the sea and went to Britain.

I found a small ‘green’ community in the Welsh hills, far away from civilisation. I stayed there for months – which turned into years. They grew their own produce; they had goats for milk and cheese, and sheep for wool. The resident herbalist ran a weekly class – women only – in natural remedies.

I had never heard of women’s shelters, or of women’s rights.

I had never even heard of the Ladies of Llangollen.

I began to look after the goats and the sheep and the dogs and cats; then other people started bringing me their animals. Soon I had a small herbal animal hospital on my hands.

But I didn’t find my true vocation until that night when I went to my first hunt saboteurs’ meeting.

In each hunter I saw my suitor, and I screamed No! at more of them than I could count. It was a word I had to learn like a foreign language, like a musical instrument, and I enjoyed using it in all its nuances. I whispered it and shouted it, sang it and screeched it; I said it cajolingly and threateningly, with irony and amusement and joy and in hot fury.

I loved every minute of it.

I was free.

D

But I had no idea what to do next.

I tried to imagine explaining to my mother (to Maelor’s mother, for that matter) what had happened. I wasn’t sure which bit they would find harder to believe: the fact that the most eligible bachelor of Cwmcapel had tried to force me, or the fact that I had deep-frozen him for his pains.

Of course he’d never do that, my dear. You must have imagined it. Are you sure you haven’t had a drop too much of that French wine?

Come on now, dear, unfreeze him. You’ve had your joke, and I’m sure I don’t know how you did it. Very clever, of course. But think how cold the poor boy must be by now.

God, but he looked stupid, even through inches of ice.

In the end, I left him there in the rose garden and just walked away.

It was a lovely summer’s night, warm and balmy and smelling of hay and dust and, faintly, salt and seaweed.

I walked and walked, and when morning came I had arrived at the seashore. There was a small island just off the coast, and I took off my satin shoes that were falling to bits, hitched up what was left of my dress and waded across.

Finally alone.

There was a well with sweet water on the island, and wild brambles and even an apple tree.

Finally alone.

Over the years, I don’t quite know how, I acquired a reputation as a wise woman who could make and unmake spells, see into the future and cure afflictions in humans and beasts.

I suppose the story of what had happened to Maelor helped a bit.

It was mostly women who came to see me and ask me for advice. I gave them my apples and a drink from the well, and they left, strengthened and comforted, and spread the word.

For twenty years and more, I was happier that I’d ever been. After that, I sometimes dreamed of the world again. Never of Cwmcapel, and not often of other places, but just sometimes I wondered what it might be like somewhere else, across the water in other co

untries. What it might be like meeting other people.

I had companions, of course. There were the seals who’d lie for hours on the rocks in the sun, and at night threw off their skins and came ashore to dance.

There were birds, crows and gulls mostly, who would sit in the tree and entertain me with stories of what they’d seen and heard.

There were quite a few cats, and a couple of donkeys and an old, wise, moth-eaten sheep.

After another twenty years, I decided I needed a change from my island life. I packed some ripe apples, filled a flask with water and waded ashore for the first time in four decades. I turned round and round with my eyes closed and finally chose a direction that seemed promising.

M

They didn’t like it, of course. And not just the hunters. In some places it was half the village that would slam its doors in our faces when we came to shop for something that we couldn’t grow, or to visit a friend or the library. Some men spat when they saw us; and even some of the children jeered.

If we thought a fox or a hare or a bird was that important, they said, we could go and ask them for ink or butter or clothes.

But they still brought their animals to us when the vet had given them up.

Then we heard rumours of what they called a counter attack.

They came one morning, quite early; a group of horsemen, and women too, in pink coats, all thundering hooves and sweaty, nervous horses and baying dogs. They scared the goats and the sheep and the sick animals in the hospital.

They scared us, too, with their lashing words and the way some of them looked at us, looked us over. I’d never realised before in quite that way that we were all of us women in the community. I didn’t think the pink-coated, purple-faced women would be much help.

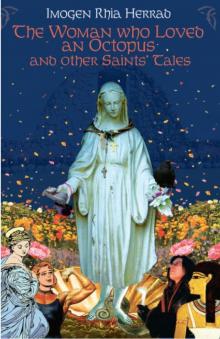

The Woman who Loved an Octopus and other Saint's Tales

The Woman who Loved an Octopus and other Saint's Tales